Plants cannot move. When exposed to drought, salinity, or other environmental stresses, they cannot escape; instead, they must rely on an intricate internal “survival system.” With global warming intensifying, abiotic stresses are expected to impose even more severe challenges to agricultural production. For decades, Dr. Wan-Hsing Cheng at the Institute of Plant and Microbial Biology, Academia Sinica, has devoted his career to understanding how plants cope with such stresses. His research explores sugar signaling, plant hormones, stress physiology, and ribosome biogenesis, revealing the molecular mechanisms that enable plants to survive stress. As he approaches retirement, Dr. Cheng reflects in a gentle, steady tone on a lifelong research path intertwined with plants.

Dr. Cheng grew up in a rural farming environment, where agricultural work was part of everyday life and naturally fostered his affection for plants. He recalls:

“I grew up in the countryside. Working in the fields was part of daily life, and naturally, I developed a deep connection with plants.”

During his undergraduate and master’s studies in horticulture, he gained practical knowledge in crop cultivation and management. It was during his master’s degree that he first encountered plant tissue culture, studying somatic embryogenesis and adventitious shoot formation. The totipotency of plant cells, much like stem cells in animals, fascinated him; a single cell dividing and differentiating into a complete embryo revealed the remarkable complexity within plants. Yet horticulture alone could not explain the genetic and biochemical pathways underlying plant development and stress responses. Seeking a deeper understanding of plant productivity and abiotic stress tolerance, he turned toward genetics and molecular biology, pursuing a Ph.D. and later a postdoctoral research position in the United States.

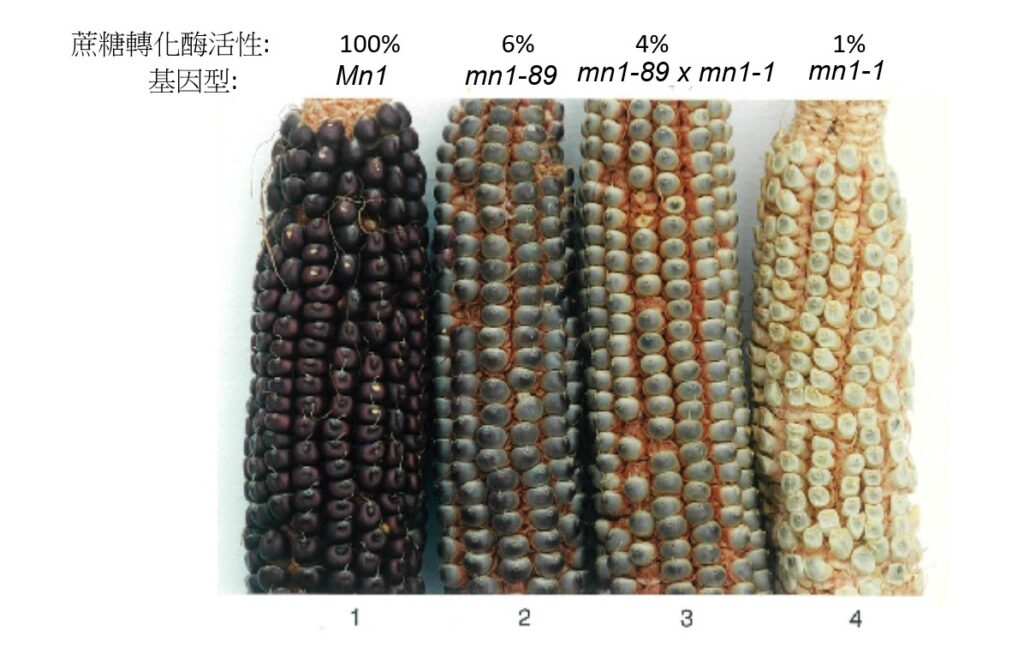

During his time abroad, his initial work focused on sucrose metabolism (Figure 2, maize) and sugar signaling. He found that in plants, sugars act not only as energy sources but also as signaling molecules, equipped with receptors and downstream signaling pathways, performing roles similar to hormones.

Invertase converts sucrose into glucose and fructose for metabolism. Defect in invertase activity due to mutations causes decreased invertase activity and reduced seed size—Mn, miniature gene; mn1-89 and mn1-1, different mutant alleles. (https://doi.org/10.1105/tpc.8.6.971)

“Abnormal sugar metabolism in humans leads to diabetes; in plants, defects in sugar metabolism or signaling also disrupt the regulation of abscisic acid (ABA), a key hormone in stress responses. Interestingly, humans also possess ABA, and its function is linked to diabetes,” he explains.

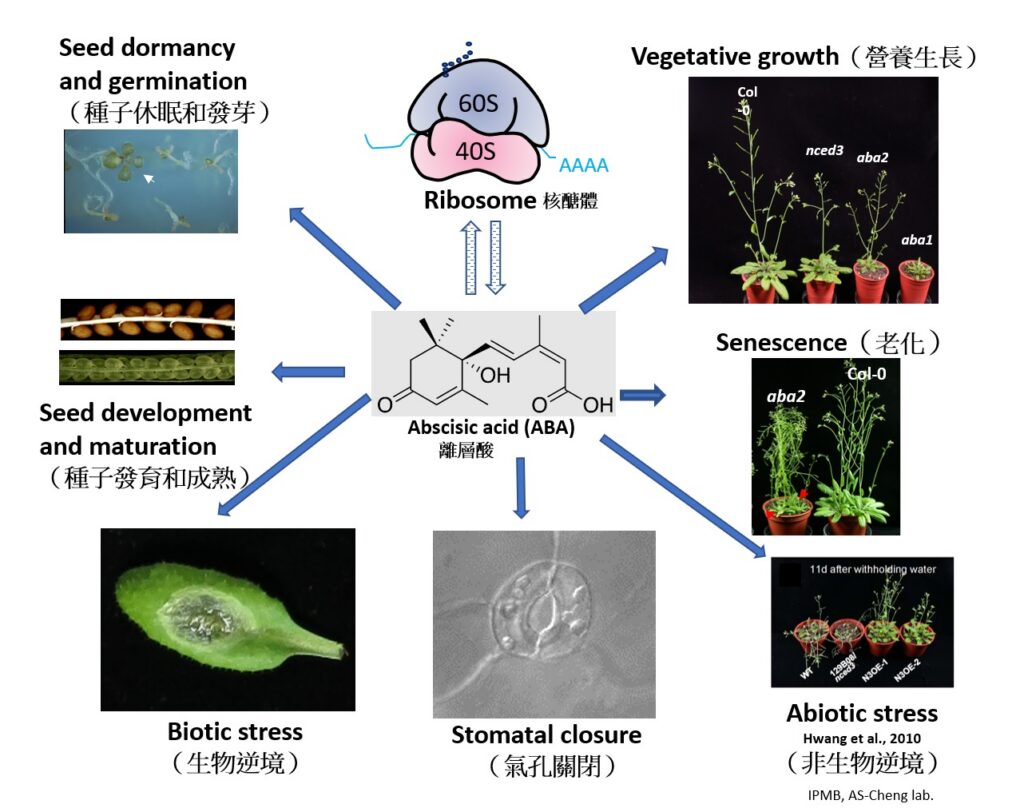

This period of research laid the foundation for the trajectory of his later work. After returning to the Institute of Botany (now called the Institute of Plant and Microbial Biology), he naturally shifted his focus from sugar signaling to ABA, using ABA as an entry point to investigate the broader regulatory networks that govern how plants respond to abiotic stress (Figure 3, Physiological functions of ABA).

Abscisic acid (ABA) is one of the most important plant hormones, which is involved in seed maturation, dormancy, plant growth and development, and stress resilience. ABA may affect ribosome-mediated protein translation; likewise, ribosomes regulate ABA biosynthesis and signaling through differential translation under adverse environmental conditions.

After returning to Academia Sinica, Dr. Cheng continued exploring the research area he started during his postdoctoral studies. He focused on manipulating ABA biosynthesis as a starting point to investigate how plants activate survival mechanisms in response to environmental stresses such as drought and salinity. Under abiotic stress conditions, endogenous ABA levels rise, enabling the hormone to regulate ion transporters on guard cell membranes, increase cellular osmotic pressure, promote stomatal closure, and reduce water loss. ABA also induces the expression of osmoprotective proteins, such as LEA proteins and dehydrins, and elevates the accumulation of osmolytes, including proline and glycine betaine, thereby helping stabilize cellular structures and maintain normal metabolic activity. In addition, ABA activates the SOS (Salt Overly Sensitive) signaling pathway as well as various secondary messenger systems, including Ca²⁺ and reactive oxygen species (ROS), to regulate downstream stress-responsive genes, enabling plants to better adapt to adverse environments. Overall, these functions make ABA an indispensable regulator of plant responses to abiotic stress.

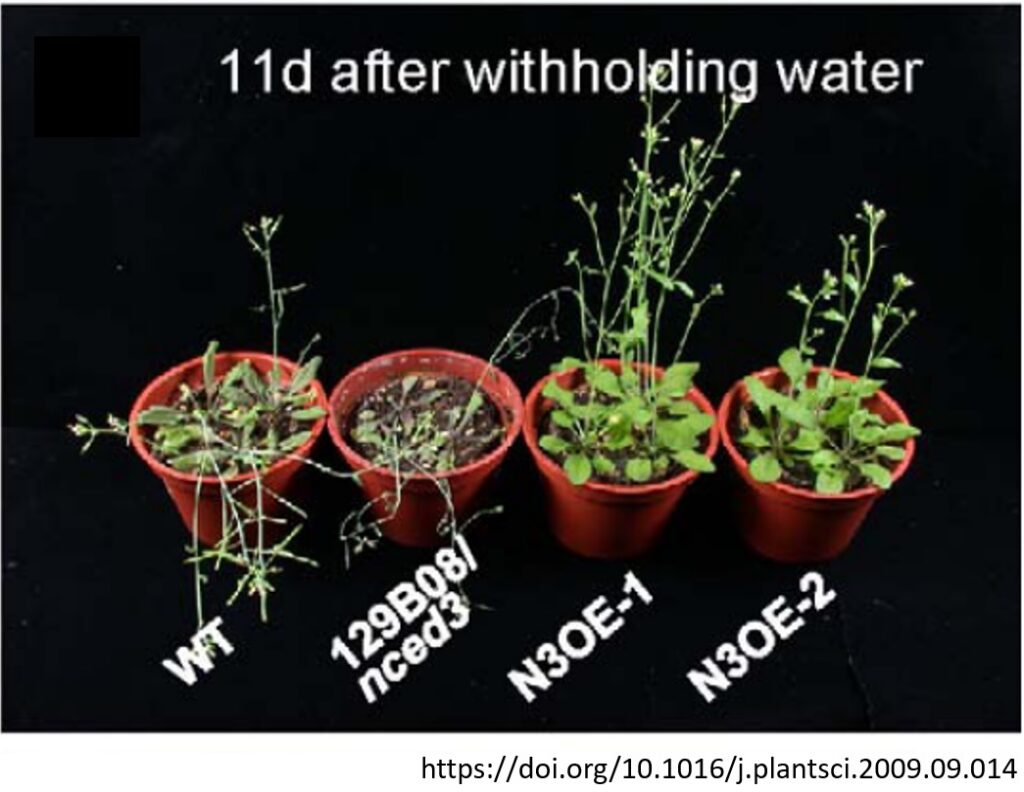

Dr. Cheng also successfully generated transgenic plants with enhanced stress tolerance by manipulating ABA biosynthetic genes (Figure 4), demonstrating a direct link between ABA levels and stress resilience. Interestingly, he observed that excessive ABA accumulation resulted in smaller plant size—an unexpected finding that highlights the inherent asymmetry and complexity of hormonal regulation in plants.

WT, wild-type; nced3, a mutant allele, N3OE, NCED3 overexpressor; NCED3, nine-cis-epoxycarotenoid dioxygenase.

“Plants often remind us that things are never as simple as they seem.”

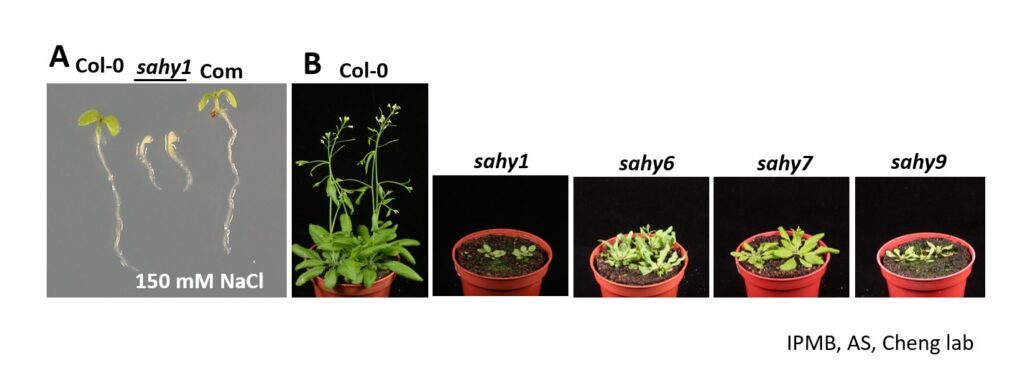

In his search for genes beyond ABA that might contribute to salt tolerance, Dr. Cheng obtained more than ten thousand Arabidopsis T-DNA insertion mutants from the Arabidopsis Biological Resource Center (ABRC, Ohio). He sowed these seeds on salt-containing media and ultimately identified 10 mutants that exhibited extreme hypersensitivity to salinity. These were designated as salt hypersensitive (sahy) mutants (Figure 5). Remarkably, three to four of these mutants had defects in genes involved in ribosome biogenesis—a surprisingly high proportion (30–40%). This unexpected finding shifted his research focus toward a relatively unexplored area: the role of ribosomes in plant responses to salt stress.

A, sahy1 mutant grown on salt-stressed medium. Com, a complemented transgenic plant.

B, sahy mutant phenotypes. Four sahy mutants defective in ribosome biogenesis are shown. Col-0 is the control.

The nucleolus and ribosomes function not only as protein factories but also as command centers that help plants sense and respond to stress.

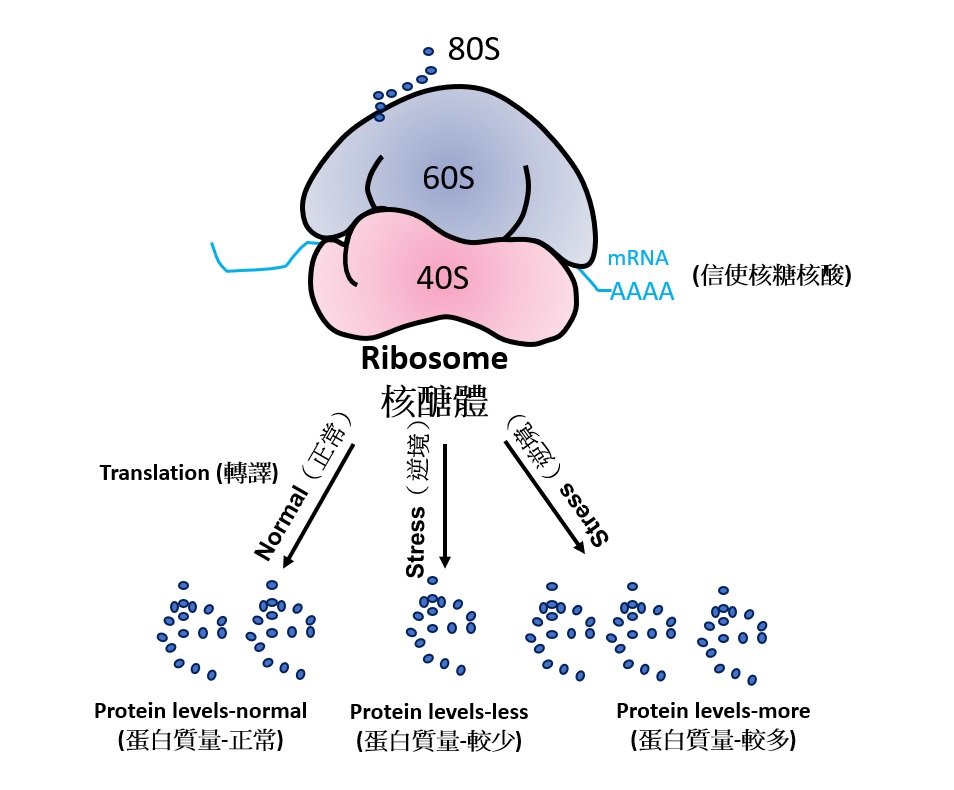

Traditionally, ribosomes have been regarded simply as cellular “protein factories.” However, emerging research has revealed that ribosomes are far more than passive production lines; they also function as sensors capable of adjusting how the factory operates. When plants encounter environmental stress, both the nucleolus and ribosomes can sense these changes and assemble ribosomes with slightly modified compositions. This process influences which mRNAs are preferentially translated and which are repressed. Such differential translation (Figure 6) enables plants to prioritize the synthesis of protective proteins under stress conditions, thereby enhancing their resilience and survival.

Under normal growth conditions, ribosomes translate proteins; however, under stress conditions, they may exhibit differential translation of specific mRNAs.

Studying ribosomes is no easy task. As Dr. Cheng notes, “Genetic approaches often take a longer time, but they are ultimately the most reliable.”

Throughout his exploration of ribosome biology, Dr. Cheng has faced numerous challenges. For example, current studies suggest that ribosomal mutants may share a common signaling pathway, as many of them display similar phenotypes. To test this hypothesis, his team subjected the sahy1 mutant to further EMS mutagenesis and unexpectedly identified a suppressor mutant that restored normal growth. This secondary mutation, referred to as the sahy1 suppressor, has yet to be fully mapped to its causal gene. Additionally, his laboratory was the first to identify a ribosomal-protein chaperone in plants. Beyond escorting ribosomal proteins to their assembly sites, this chaperone can also interact with other protein classes, such as tubulins, indicating a broader functional diversity than the ribosomal-protein chaperones previously described in yeast and humans. This discovery highlights the unique diversification of ribosome biology in plants.

Reflecting on his research career, Dr. Cheng highlights four achievements that left a lasting impression on him.

First, manipulating ABA biosynthetic genes successfully enhances plant stress tolerance, although unexpectedly, excessive ABA accumulation results in smaller plants.

Second, his team found that protein glycosylation plays a role in modulating plant tolerance to environmental stresses.

Third, the sahy mutants demonstrated that ribosomes are key players, perhaps like sensors, in stress responses.

Fourth, his team’s discovery of a multifunctional ribosomal-protein chaperone in plants opened a new research avenue.

Together, these findings cover hormone signaling, stress physiology, and ribosome biogenesis, forming the main themes of Dr. Cheng’s scientific journey.

Life beyond research: exercise, nature, and new beginnings

When discussing life outside the lab, Dr. Cheng explains that a PI’s workload is often intense, with experiments, mentoring students, writing grant proposals, and preparing manuscripts easily filling an entire day. To stay balanced, he established a routine of regular exercise, including swimming, jogging, and hiking. Physical activity keeps him healthy, but more importantly, it helps him stay focused and mentally sharp despite a demanding research schedule.

“As with doing research, these interests have simply become part of my everyday life, and they require perseverance and consistency,” he says. His life philosophy is equally grounded and humble: “Do your best, and let the outcome take care of itself.”

As he approaches retirement, Dr. Cheng admits that it is hard to leave behind the research he has devoted decades to. Yet he also looks forward to slowing down and rediscovering a different rhythm. He hopes to spend more time in nature, feeling the seasons shift, walking through the mountains, and cultivating flowers and plants as a quiet leisure activity. He also plans to keep reading the latest scientific journals, not out of duty but because it has long been a genuine interest and habit. In addition, he hopes to hike several of Taiwan’s Xiao-bai-yue (Taiwan 100 Minor Peaks, Figure 7), extending his long companionship with plants into a new kind of journey through the mountains.

The top of Dajian Mountain Trail offers views of Taipei city, Xizhi, and Keelung areas, including the 101 building and Keelung Island.

When offering advice to IPMB and young researchers, Dr. Cheng emphasizes the importance of balanced growth within the institute. For young scientists, he highlights the need for solid foundational knowledge, a sharp eye for identifying experimental problems, and the ability to resolve them efficiently. Equally important, he says, is learning how to collaborate, since many scientific questions require cross-disciplinary and cross-technical cooperation. He leaves a particularly memorable message:

“Treasure the exceptions that will bring you surprises or miracles.”

To him, those observations that “don’t quite fit expectations” are often the starting points of real breakthroughs.

Dr. Wan-Hsing Cheng’s scientific journey moves from the visible parts of plants to their hidden interior worlds, from the fields of his childhood to the nucleolus inside a plant cell. It is a story woven with patience, perseverance, and curiosity. His contributions and enduring passion for science will continue to influence the field of plant biology and inspire new generations of researchers for years to come.