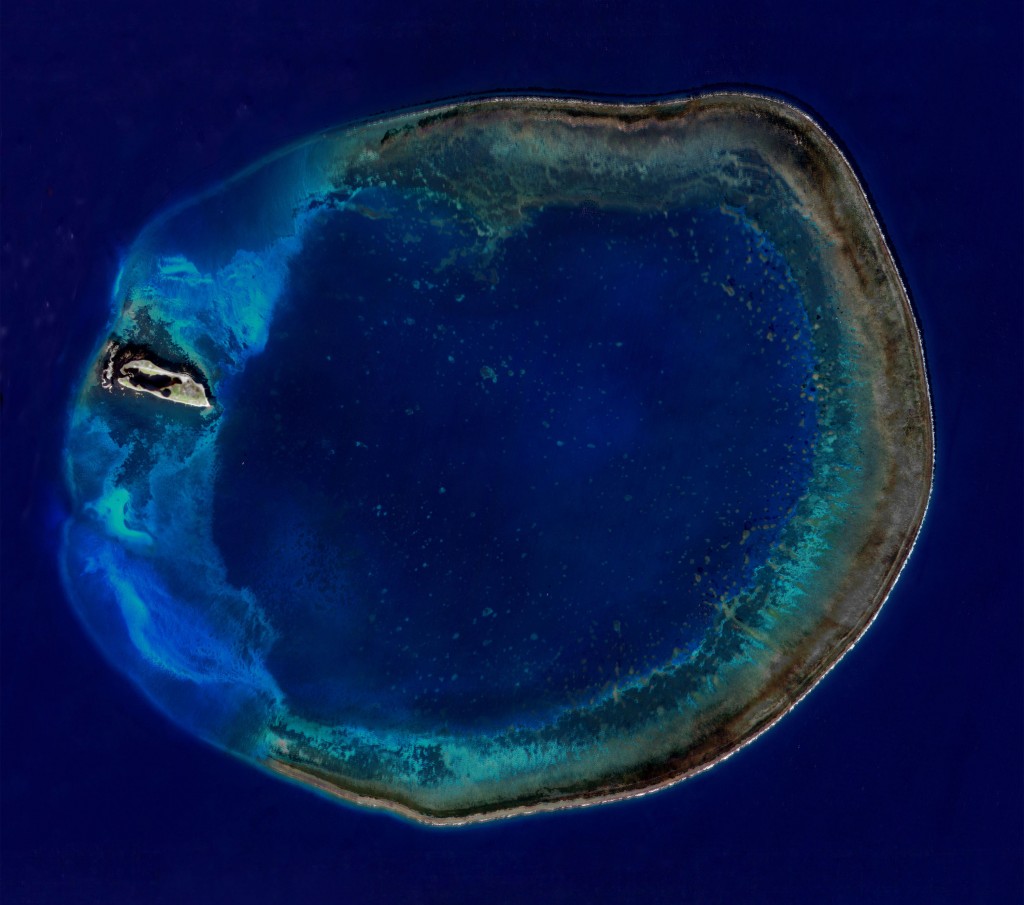

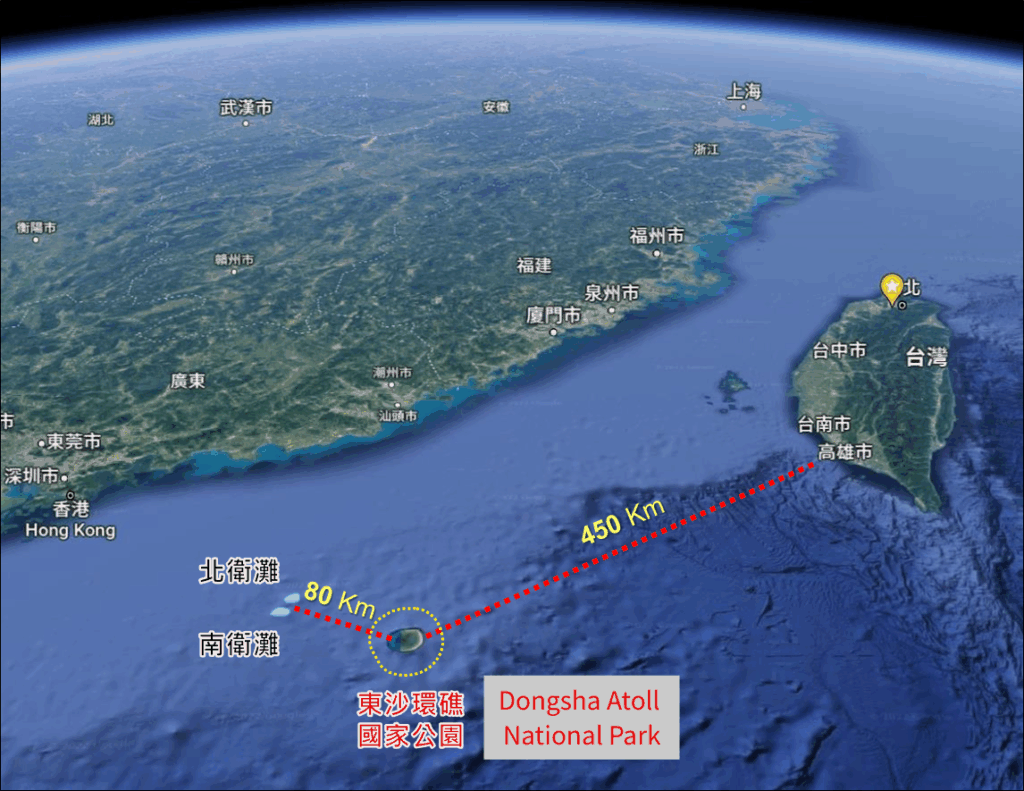

On the map of Taiwan, Dongsha Island appears as little more than a tiny dot in the South China Sea. More than 400 kilometers away from Kaohsiung, this remote island has no bustling city, no fishing harbor, and no permanent residents. Shaped like a horseshoe and built from coral reefs, Dongsha covers less than two square kilometers of land. For decades it has been guarded only by the Coast Guard, serving both as a strategic outpost and as a designated ecological reserve. Dongsha Atoll is formed entirely of coral, with Dongsha Island on its western edge. The island is the only piece of land that remains above water at high tide. At its center lies a small lagoon (20° 70’N, 116° 80’E) with an average depth of just about one meter. Beneath its calm surface lie some of the harshest environmental conditions on Earth.

What seems like a calm pool of water is, in fact, nature’s trial ground for survival.

Unlike the surrounding sapphire-blue ocean, conditions inside the lagoon are extreme. While surface water temperatures around Dongsha Atoll in a year are between 22 and 32 °C, the lagoon stays above 35 °C during daytime and can rise over 38°C in summer—hotter than some hot springs. Its salinity often climbs far beyond the ocean’s average of 3.3-3.5%. The combination of high temperature and fluctuating salinity makes survival difficult for most marine life.

To most people, this may look like nothing more than a body of hot, salty water. But to scientists, it poses another challenge: can life really survive under such extreme conditions?

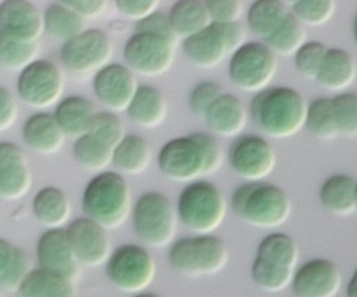

The answer lies with a hidden community of cyanobacteria, quietly thriving in the lagoon and serving as the primary producers of its ecosystem.

These microscopic cells not only survive but flourish, treating this extreme habitat as their everyday home. One such unicellular marine cyanobacterium, Cyanobacterium sp. Dongsha4 (DS4), has mastered the art of survival in harsh conditions. Even as temperatures approach 50 °C, DS4 continues photosynthesis unaffected. It withstands salinity far above that of normal seawater. And when organic nitrogen, an essential nutrient, is scarce, it simply performs its own nitrogen fixation, persisting quietly under scorching sunlight and in salty waters. Compared to the green algae and seaweeds we know, these cyanobacteria are like ancient survivors of evolution, true “survival experts” that have endured for millions of years.

This discovery was made by Dr. Hsiu-An Chu and Dr. Chih-Horng Kuo of the Institute of Plant and Microbial Biology, Academia Sinica, together with Prof. Ching-Nen Nathan Chen of National Sun Yat-sen University. Through whole-genome sequencing and physiological analyses, the team found that DS4 possesses a unique “genetic toolkit” for withstanding heat, salt, and nutrient scarcity, and may even hold potential for the development of new antimicrobial compounds.

Whole-genome analysis has revealed that DS4 carries many remarkable features. Based on the 16S rRNA gene, DS4 shares 99.9% sequence similarity with Cyanobacterium sp. NBRC 102756 from Japan and Cyanobacterium sp. MCCB114/115/238 from India. However, since the full genome data of NBRC 102756 and MCCB114 are not yet available, detailed comparative analyses cannot be performed. Among cyanobacteria with published genome sequences, DS4 is most closely related to Cyanobacterium aponinum PCC 10605 from an Italian hot spring, with 92.9% average nucleotide identity. DS4 is therefore considered a newly identified species with unique genetic traits, including a complete set of nitrogen-fixation genes and multiple stress-response genes, that enable it to thrive under extreme environmental conditions.

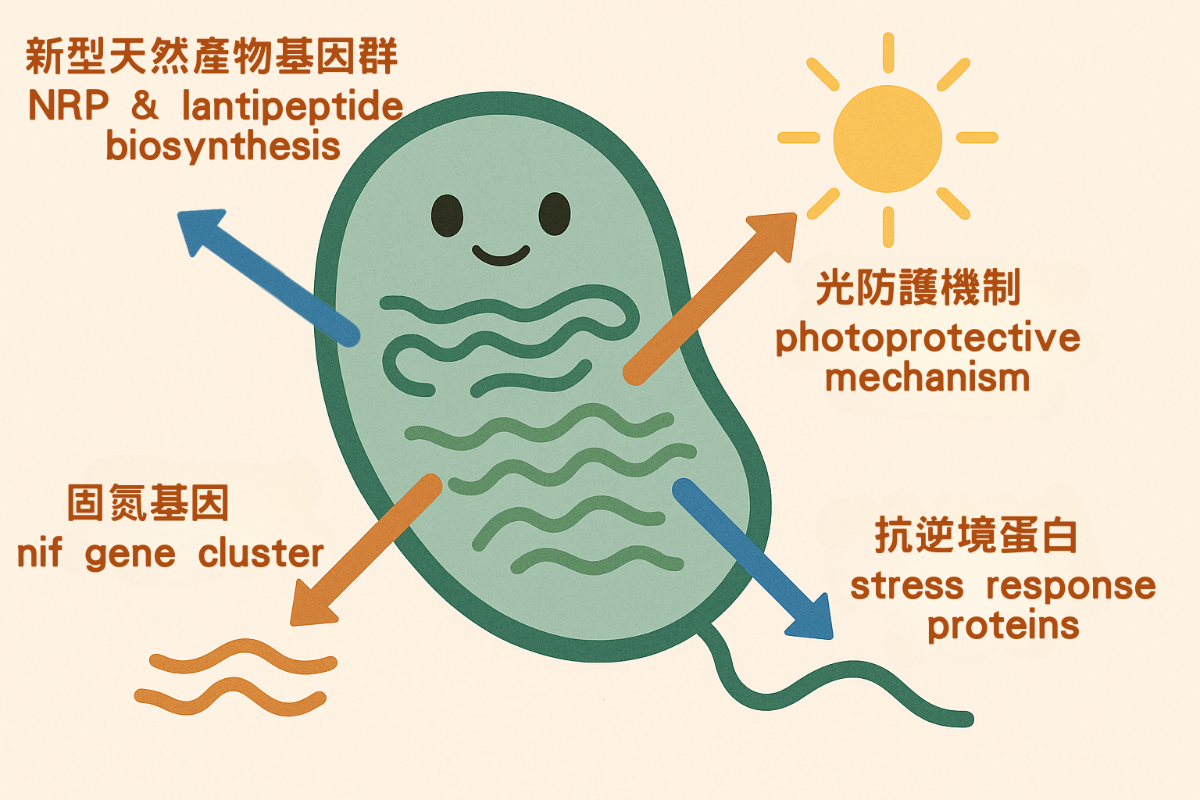

First, DS4 carries a complete nif gene cluster for nitrogen-fixation, which allows it to convert atmospheric nitrogen or inorganic compounds into the essential nutrients it needs, even in environments lacking external sources of organic nitrogen. This self-sufficient ability means it does not rely on nutrient-rich waters from outside and can survive steadily in the nutrient-poor, high-salinity lagoon.

DS4 is also equipped with multiple genetic tools to combat harsh conditions. Among them are numerous chaperone genes, which help maintain the proper structure of proteins under heat or salt stress, preventing them from becoming damaged or losing function. These adaptations enable DS4 to remain physiologically stable even under extreme environmental stress.

In addition, to withstand intense sunlight, DS4 has developed a specialized photoprotection system. Within its cells, it carries orange carotenoid binding protein (OCP) that helps reduce damage to the photosynthetic machinery under strong light. At the same time, antioxidant enzymes remove reactive oxygen species, protecting the cells from harm caused by sunlight and oxidative stress. This system enables DS4 to maintain stable photosynthesis even after prolonged exposure to high light and high temperatures, allowing it to withstand extreme conditions without being overwhelmed.

Even more remarkably, the genome of DS4 harbors the potential to produce novel natural compounds. Researchers discovered gene clusters for the biosynthesis of nonribosomal peptide (NRP) and lantipeptides—small molecules that often serve antimicrobial, inhibitory, or signaling functions in nature. These compounds may one day serve as promising sources for new drugs or biomaterials.

Together, these traits form a comprehensive “survival toolkit” that not only allows this cyanobacterium to thrive in Dongsha’s extreme lagoon, but also challenges us to rethink the potential of life in harsh environments.

In the harsh environment of Dongsha’s lagoon, scorched by intense sunlight, subject to dramatic shifts in salinity, and seemingly unfit for life, DS4 relies on a finely tuned genetic toolkit to endure heat, salt, and nitrogen scarcity. These genetic traits are not only keys to its own survival but also reflect the deep wisdom accumulated through billions of years of evolution. In a sense, these microbes may be rehearsing the very strategies that could allow life to persist under extreme conditions.

The genetic capabilities and specialized metabolic pathways of DS4 also open new possibilities for future science, environmental applications, and biotechnology. In the face of climate change, resource depletion, and uncertainty ahead, perhaps we can borrow a measure of resilience from these microscopic forms of life.

[Source]

Ching-Nen Nathan Chen, Keng-Min Lin, Yu-Chen Lin, Hsin-Ying Chang, Tze Ching Yong, Yi-Fang Chiu, Chih-Horng Kuo & Hsiu-An Chu (2025) Comparative genomic analysis of a novel heat-tolerant and euryhaline strain of unicellular marine cyanobacterium Cyanobacterium sp. DS4 from a high-temperature lagoon. BMC Microbiology 25:279.

https://bmcmicrobiol.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12866-025-03993-7