After the autumn rice harvest, golden stalks are left lying along the edges of the fields, waiting to be burned. Wood chips from sawmills, sugarcane bagasse from mills, and fruit peels left over from juice production are also discarded as if they had no value at all. Each year, more than 140 billion tons of plant waste accumulate around the world—enough to stack dozens of Taipei 101 towers. If all of this biomass could be fully converted into fuel, the output would be sufficient to power our planet for nearly eighty years. Because of current technological and processing limitations, this vast resource is mostly left to ferment, burn, or decay, ultimately turning into smoke and wasted energy.

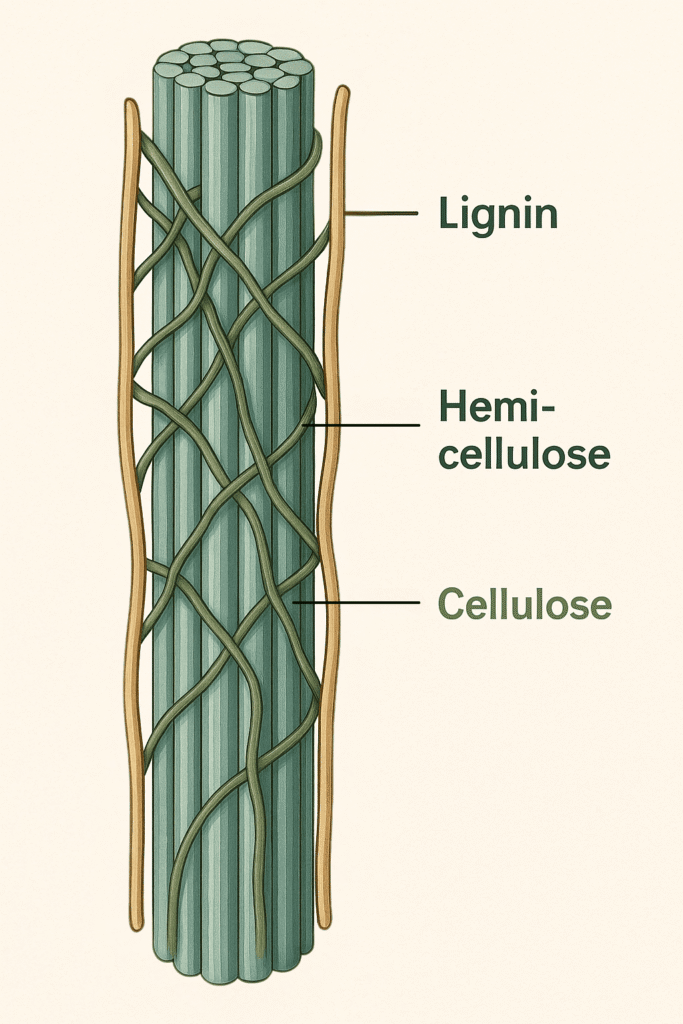

Plants are not easy to break down. Their tissues are protected by a natural armor that makes it extremely difficult for any organism to access. This protective layer is known as lignocellulose, the most abundant and one of the most resilient biological materials on Earth. It is found in nearly all plant cell walls so plants can resist wind, rain, and pests. It also creates one of the biggest barriers in converting plant biomass into usable energy. Lignocellulose is made up of three major components: cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin. Cellulose serves as the structural backbone. Hemicellulose forms the adhesive matrix that holds the cellulose fibers together. Lignin acts as a tough, water-resistant outer shield. These components are tightly interwoven, forming a remarkably sturdy protective structure that is very difficult to break apart.

Cellulose forms the central structural fibers, hemicellulose wraps around them like a supportive network, and lignin creates the tough outer layer that protects the cell wall.

To crack this tough armor, scientists turn to nature’s expert decomposers, including microorganisms that quietly break down plant material from rotting wood, deep soil, and even the stomachs of cows. Among these organisms, bacteria and fungi are remarkably effective at degrading plant fibers, although with very different strategies.

Bacteria use a cellulosome, a scaffoldin-based structure that holds many enzymes together to break apart plant fibers. Fungi take a different approach by releasing oxidative enzymes that open up the lignin barrier on the outside of the plant cell wall.

One of the most remarkable systems comes from bacteria: the cellulosome. This multi-enzyme complex acts like a miniature factory built to deconstruct cellulose and hemicellulose. At its center is a scaffoldin protein, which serves as the structural backbone that organizes dozens of enzymes in a tightly packed arrangement. By surrounding the plant fiber and working together in one place, these enzymes achieve high efficiency. This coordinated mode of action can be up to fifty times faster compared to freely secreted enzymes. Bacterial cellulosomes can also adjust their enzyme composition depending on the type of plant materials. For example, when bacteria grow on substrates with higher lignin content, such as pine pulp, they increase the production of supporting enzymes like xylanases and mannanases, which help remove polysaccharides around lignin-rich regions. This adaptive flexibility allows bacteria to respond effectively to a wide range of plant residues.

In the usual situation (top), enzymes float freely and work individually. In a cellulosome (bottom), many enzymes are anchored to the same scaffoldin, allowing them to work side by side and greatly increase degradation efficiency.

Scientists later discovered that certain anaerobic fungi living in the stomach of cows and sheep have also evolved a system like a fungal version of the cellulosome, although research on it is still in its early stages. Fungi are particularly notable for their ability to break down lignin. They secrete a wide range of oxidative enzymes, such as laccases and peroxidases, which attack the chemical bonds in lignin and gradually dismantle this tough protective layer into smaller molecules. Different groups of fungi also play different roles. White-rot fungi have a full set of lignin-oxidizing enzymes, brown-rot fungi rely on reactions involving reactive radicals, and soft-rot fungi are active in the later stages of fiber degradation. In some cases, fungal species may even share enzymatic tools, allowing enzymes from different species to work together during the breakdown process.

A recent study led by Dr. Pao-Yang Chen at the Institute of Plant and Microbial Biology, Academia Sinica, aims to better understand how bacteria and fungi break down lignocellulose. His team systematically compared the enzyme sets and operating mechanisms these organisms use during lignocellulose degradation. Their results show that although bacteria and fungi are evolutionarily distant in both their enzyme repertoires and the protein sequences of their cellulosome-like components, they have convergently developed a similar functional strategy: bringing together multiple enzymes and organizing them into a cooperative system.

The study also highlights two major design features that distinguish fungal cellulosomes from their bacterial counterparts. First, fungal systems are more flexible. Their enzyme-binding modules do not require the one-to-one matching seen in bacterial systems. Instead, components from different fungal species can interact with one another, allowing them to be shared across species. This flexibility likely helps fungi assemble efficient degradation complexes in highly variable environments. Second, fungal cellulosomes possess the most extensive collection of carbohydrate-active enzymes (CAZymes) identified so far, including several types absent from bacterial systems. One example is the β-glucosidases GH3, which enables fungi to convert cellulose directly into monosaccharides. These features give fungi a particular advantage when facing with tougher, more resistant plant materials, especially those with a high lignin content, and highlight their strong potential for future biotechnological applications.

Inspired by these microbes, scientists have been working to build designer cellulosomes, artificial versions of the natural systems used by microbes to break down plant biomass. Current designs are mostly based on the well-studied bacterial species A. thermocellum and A. cellulolyticus. Experiments have shown that cellulosomes engineered from these bacteria can break down crystalline lignocellulose two to three times more efficiently than free enzymes. One major advantage of designer cellulosomes is that they allow enzymes from different bacterial species to be assembled on the same platform. Scientists can combine the bacteria’s native cellulosomal enzymes with additional enzymes, further improving the overall degradation efficiency.

However, designer cellulosomes still face a major challenge: the attachment between enzymes and the scaffoldin is not stable enough. If the connection becomes unstable, the structure can fall apart, reducing the efficiency of lignocellulose degradation. To address this, researchers are now using improved versions of AI tools such as AlphaFold 3 to model the 3D structures of proteins and to efficiently evaluate their interactions, allowing researchers to identify the most stable combinations in silico to build more stable “degradation factories.”

Perhaps the future energy factories will look nothing like today’s smoke-filled refineries. Instead, they may be quiet bioreactors powered by microbes. The entire process would have less pollution, and the resulting fuel would be clean, renewable, and highly efficient. One day, the fuel in our cars may not come from deep underground, but from leaves and plant broken down by microbes in the forest.

[Source]

Lignocellulose degradation in bacteria and fungi: cellulosomes and industrial relevance

Kuan-Ting Hsin(辛冠霆), HueyTyng Lee(李卉婷), Yu-Chun Huang(黃郁珺), Guan-Jun Lin(林冠均), Pei-Yu Lin(林蓓郁), Ying-Chung Jimmy Lin(林盈仲), Pao-Yang Chen*(陳柏仰) (2025)

Frontiers in Microbiology, https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2025.1583746