Viruses pose a major threat to human health and food security, while also shaping the rise and fall of life within natural ecosystems. They not only cause a wide range of diseases in plants and animals but also influence the population dynamics of algae and other microorganisms in diverse ecosystems. Yet some of the most fundamental questions remain unanswered: How long have viruses existed on Earth? When did they originate, and how have they co-evolved with their hosts? Unlike plants and animals, which leave evolutionary traces in the form of fossils, viruses have no bones and leave no marks in the geological record. As a result, their evolutionary history has long been shrouded in mystery.

In recent years, scientists have turned their attention to an extraordinary group of viruses—giant viruses. These viruses possess remarkably large and complex genomes, which can carry more genes than some bacteria. They infect a wide variety of eukaryotic organisms, including animals, fungi, algae, amoebae, and flagellates, and play crucial roles in ecosystem dynamics. Determining the “birth time” of giant viruses allows researchers to place them back on the geological timeline and better understand their significance in Earth’s history.

To overcome the challenge posed by the lack of viral fossil records and calibration points, Dr. Chuan Ku and his research team at the Institute of Plant and Microbial Biology, Academia Sinica, developed a novel host-calibrated dating approach. This method uses the ages of eukaryote host taxa as calibration points for estimating viral divergence times. Giant virus clades are known for their strong host specificity: some infect only vertebrates, others target insects, and some others infect a specific algal lineage. Because of this tight host-virus relationship, the appearance time of a host can be used to infer the earliest possible origin of its associated viruses. For instance, if a group of giant viruses infects only birds, their last common ancestor must have emerged after birds appeared on Earth. Likewise, if a viral lineage is exclusive to Lepidopteran insects, those viruses cannot predate their hosts (butterflies and moths). In short, the emergence of the host constrains when the virus itself could have originated.

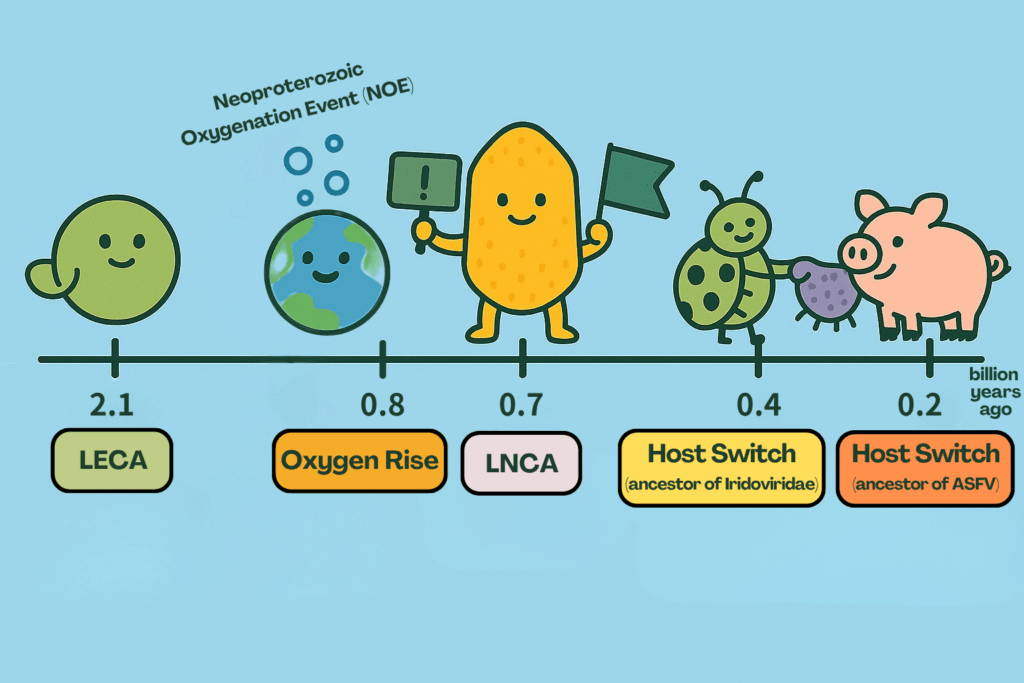

The team compiled the divergence times of various host taxa based on global databases of eukaryote fossils or phylogenies and used them for 45 calibration points across the giant virus phylogeny. By analyzing these time markers with the branch lengths of the viral evolutionary tree, they reconstructed a time-calibrated phylogeny—a timeline of viral diversification. The results were striking: the last common ancestor of the giant viruses (i.e., the last Nucleocytoviricota common ancestor, LNCA), was estimated to have emerged around 700 million years ago, which was at least one billion years after the last eukaryotic common ancestor (LECA, approximately 2.1 billion years ago). This finding shows that giant viruses were not ancient parasites or a fourth domain of life, but rather latecomers that rose to prominence much later in Earth’s history.

Giant viruses are much younger than eukaryotes and have a remarkably dynamic history. Over evolutionary time, they underwent several major host-switching events, transitioning from amoebozoan hosts to animals. These shifts reshaped their evolutionary trajectories and gave rise to important pathogens such as African swine fever virus, which has devastating impacts on pig farming industry, and members of the family Iridoviridae, which infect insects, crustaceans, and various vertebrates.

Intriguingly, the estimated emergence of giant viruses coincides with the Neoproterozoic Oxygenation Event (NOE), a period marked by a dramatic increase in oxygen on Earth. This surge fueled the rise of multicellular eukaryotic life and may have also enabled giant viruses, which rely heavily on their hosts’ mitochondrial metabolism for energy, to thrive. In other words, without that great oxygenation event, giant viruses might never have appeared on Earth at all.

Beyond host switching, the genomes of giant viruses are fascinating in themselves and can be described as mosaics assembled from genes of diverse origins. Many seem to come directly from eukaryotes, and some genes appear to have been borrowed from bacteria, archaea, or even other viruses. This genetic patchwork makes the giant viral gene repertoire extraordinarily diverse and, in some cases, “ancient” in appearance.

It is also notable that the evolutionary rates of giant viruses are far from uniform. Among poxviruses (Poxviridae), for instance, mammalian poxviruses (such as smallpox and mpox viruses) evolve the fastest among Nucleocytoviricota lineages, whereas crocodilepox virus evolves nearly two orders of magnitude more slowly. These disparities reveal that viral evolution is far more complex than a simple molecular clock, and that understanding their true timescales requires a broader evolutionary framework.

Although giant viruses were not among the earliest players in Earth’s history, they appeared at just the right moment. Originating as parasites of amoebozoan hosts, they later expanded their reach to animals, algae, fungi, and other eukaryotes, eventually diversified into lineages that infect specific hosts, including humans and livestock animals. Their evolutionary journey has left a profound imprint on both ecosystems and human society. Reconstructing the time-calibrated phylogeny of giant viruses is like compiling their evolutionary chronicle: it reveals when they first appeared, when they switched hosts, and how they might have adapted to changing environments. More importantly, this research underscores how tightly intertwined viral evolution is with the history of Earth’s environment and the hosts. Understanding these connections not only enriches our picture of life’s evolution but also provides a broader perspective that may help us predict the trajectories of future emerging viruses.

[Source]

Host-Calibrated Time Tree Caps the Age of Giant Viruses

Mol Biol Evol. 2025 Feb 3;42(2):msaf033. doi:10.1093/molbev/msaf033.